Stefan Benedik, Monika Sommer: Erinnerungskultur als Frage der Gegenwart, Ausstellen als Prozess. In: Tiroler Landesmuseen (Hg.): Memories of Memories, das Lager Oradour, Salzburg-Wien 2023, 167–176.

Erinnerungskultur als Frage der Gegenwart, Ausstellen als Prozess. Reflexionen aus kuratorischen Zugängen im Haus der Geschichte der Geschichte Österreich

Stefan Benedik, Monika Sommer

Was bedeutet Erinnern an den Nationalsozialismus? Welcher Handlungsbedarf ergibt sich daraus für die Gegenwart? Das waren die beiden Fragen, die wir im Haus der Geschichte Österreich ins Zentrum rückten, als wir März 2023 den Abschnitt zur Auseinandersetzung mit den Debatten um NS-Erinnerung in unserer Hauptausstellung „Neue Zeiten: Österreich seit 1918“ neu konzipierten. Leitend für die Entwicklung dieses neuen Bereichs war nicht nur ein Perspektivenwechsel weg von den 1980er-Jahren hin zur jüngsten österreichischen Geschichte und aktuellen Kontroversen, sondern auch die Zielsetzungen, Ausstellung als Prozess zu denken, die auch nach ihrer Eröffnung noch dynamisch bleiben, Besucher*innen in deren Mittelpunkt zu rücken und dem gesetzlichen Auftrag gemäß unserem Charakter als „Diskussionsforum“ gerecht zu werden.[1] War der 100. Jahrestag der Ausrufung der Republik im November 2018 der Anlass zur Eröffnung des Museums, war diesmal der 85. Jahrestags der „Anschlussrede“ Adolf Hitlers am Altan unseres Standortes in der Neuen Burg am Wiener Heldenplatz das Datum, das wir für die Übergabe des neu gestalteten Bereichs an die Öffentlichkeit gewählt hatten – auch in Hinblick darauf, wie sehr die Erwartungen von Publikum und interessierter Öffentlichkeit zwischen der Abdeckung eines breiten Fokus auf die Zeitgeschichte insgesamt und andererseits dem Wunsch nach einer intensiven Begleitung von öffentlichen Debatten und spezifischen Vermittlungsangeboten rund um die Frage von NS-Herrschaft und den Umgang mit ihr in der Gegenwart changieren.

Manche mögen überrascht sein, dass das junge Zeitgeschichtemuseum, das 2018 nach Jahrzehnten der Diskussionen über den Sinn und die Notwendigkeit der Einrichtung eines Museums der jüngsten Geschichte seine Pforten öffnete,[2] knapp fünf Jahre später einen Teil der Überblicksausstellung mit einem völlig veränderten Zugang der Öffentlichkeit aktualisiert präsentiert. Fünf Jahre sind – so meinen wir – ein guter Zeitrahmen, um die kuratorischen Setzungen des historischen Moments, in dem eine Ausstellung nicht nur entsteht, sondern den sie auch (wenigstens implizit) abbildet, zu überprüfen und zu reflektieren, welche Narrative und Perspektiven auf die Vergangenheit auch in der Gegenwart noch produktiv sein können, also gesellschaftliche Relevanz im Heute haben. Dies ist für das Haus der Geschichte Österreich insofern von hoher Bedeutung, als es sich als ein Gesellschaftsmuseum am Puls der Gegenwart versteht.

Daher verwenden wir für die Ausstellung „Neue Zeiten: Österreich seit 1918“, die einen Überblick von der Zeitenwende 1918 bis ins Heute vermittelt, den Terminus Hauptausstellung in bewusster Verweigerung oder Weiterentwicklung des oftmals eingeführten Begriffs „Dauerausstellung“, da letzterer eine nicht einzulösende Überzeitlichkeit vermittelt, die Dynamik der Einrichtung Museums sowie seine oder ihre eigene Geschichtlichkeit negiert.[3] Darüber hinaus lässt die Bezeichnung grammatikalisch zweideutig offen, ob „eine Dauerausstellung eine auf Dauer angelegte Ausstellung ist oder Dauer ausstellt“[4], wie Sabine Offe festgehalten hat. In diesem Sinne verfolgen wir auch eine geschichtstheoretische Orientierung, die Menschen als Akteur*innen von Erinnerung ins Zentrum rückt insoferne, als Geschichte eben nicht als abgeschlossen präsentiert wird, sondern als prozesshaftes Ergebnis von Diskussionen und Verhandlungen.

Der Rahmen: Gegenwart ausstellen in einer historischen Ausstellung

Im geschichtspolitischen Feld der Beschäftigung mit NS-Erinnerungskulturen versuchten wir daher schon zwei Jahre nach der Eröffnung, im Juni 2020, durch einzelne Ergänzungen nicht nur neue Debatten aufzugreifen, sondern auch weniger prominenten Beispielen breitere Aufmerksamkeit zu verschaffen. In diesem Kontext bedeutete das die Aufnahme von Teilen der Kunstinstallation „Kein Anšluss unter dieser Nummer! 2031938“, mit der ein kärntnerslowenischen Künstler*innenkollektivs auf die lange tabuisierte Geschichte der scheinwissenschaftlichen rassistischen Erfassung der Bevölkerung der Gemeinde Šentjakob v Rožu/St. Jakob im Rosental unmittelbar vor Ort aufmerksam gemacht hatte genauso wie aus mit höchster medialer Aufmerksamkeit geführten Debatten um die Veröffentlichung einer Ausgabe der Stadtparteizeitung der FPÖ Braunau mit dem rabiat anti-islamischen „Rattengedicht“, das aufgrund seiner Übersetzung von klassisch antisemitischen Stereotypen in das diskursive Umfeld der Migrationsdebatten im Museum erlaubte, Merkmale des strukturellen Antisemtitismus zu vermitteln. Während dieses Objekt auch in der Überarbeitung 2023 noch im Museumsraum verbleibt, wanderten andere 2020 ergänzten damals neuen Objekten jetzt wieder zurück ins Depot, darunter die Objekte der erwähnten Kunstinstallation, aber auch das Manuskript der 2018 von Michael Köhlmeier gehaltenen Rede zum Jahrestag des „Anschluss“-Gedenkens.

Zur Überarbeitung 2023 waren es neben dem bereits erwähnten notwendigen frischen inhaltlichen Blick nach fünf Jahren weitere, pragmatische Aspekte, die eine Aktualisierung befördert haben. In der ursprünglichen Version des Ausstellungsbereichs wurden – auf einer raumgreifenden quadratischen Plattform versammelt – zahlreiche geschichtspolitische Debatten der Ersten und Zweiten Republik anhand ausgewählter Objekte thematisiert. In der Praxis erwiesen sich sowohl die inhaltliche Schwerpunktsetzung als auch die Gestaltung vor allem vor dem Hintergrund des beschränkten Platzangebots als verbesserungswürdig. Durch die Erfahrungen aus der intensiven Tätigkeit der Fachkolleg*innen aus dem Vermittlungsteam aus unzähligen Gesprächen vor Ort in der Ausstellung wie auch aus Workshops, wurde bereits 2019/20 sichtbar, dass die Thematisierung von geschichtspolitischen Debatten der Dollfuß-Schuschnigg-Diktatur und der NS-Herrschaft in unmittelbarer Nähe zueinander die Besucher*innen verwirrte, da sie gerade zuvor in einer linearen Ausstellungsrezeption mit dem Ausstellungsteil zur Ereignisebene von NS-Herrschaft und Zweitem Weltkrieg konfrontiert worden waren. Wir entschlossen uns demnach bereits in der ersten Überarbeitung 2020 zu einer Schärfung des inhaltlichen Fokus und konzentrierten uns beim Neukonzipieren des Thementeils auf die Auseinandersetzung mit der Rezeption der NS-Zeit. In den Jahren seit 2020 kam hinzu, dass sich die Plattform als Gestaltungselement vor allem für die Arbeit mit Gruppen nicht bewährt hatte, da zu wenig Platz für den Aufenthalt vor Objekten blieb und die ursprüngliche Situation in Hinblick auf Barrierefreiheit Verbesserungspotential aufwies. Inhaltlich hatte sich die Zweiteilung des Narrativs in hegemoniale Perspektiven (entlang der Achse von Borodajkewycz- über Kreisky-Peter-Wiesenthal- zur Heinrich-Gross- und Liederbuch-Affäre) und marginalisierten Perspektiven (von Resitutionsfragen am Fall eines zu restituierenden Opernguckers aus dem Bestand des Universalmuseum Joanneum bis zur verweigerten Anerkennung von NS-Überlebenden in der Opferfürsorge) in einer selbstkritischen Perspektive durch die dazwischen liegende große Plattform als problematisch herausgestellt, weil sie stark zusammenhängende Prozesse räumlich voneinander trennte. Ausschlaggebend für die Entscheidung zu einer völligen Neukonzeption des Themenbereichs war schließlich das Auslaufen eines befristeten Leihvertrags für ein Großobjekt, das den Bereich bisher inhaltlich und gestalterisch dominierte: das sogenannte Waldheim-Pferd, das bislang die geschichtspolitische Wende der Jahre 1986/88 bis 1991 in einer vergleichsweise überproportionalen Weise repräsentierte. Nun eröffnete sich die Chance, den Schwerpunkt zur Erinnerungskultur in Österreich neu zu gestalten und dabei auch die inhaltliche Validität dieser Zentralsetzung zu hinterfragen.

Gegenwarts- statt Vergangenheitsorientierung

Am Beginn jeder Ausstellungskonzeptionsarbeit steht im Haus der Geschichte Österreich die Frage „Was bewegt die Gegenwart?“. Diese diskutierten wir auch im Fall der Neukonzeption des Bereichs zu NS-Erinnern in einem kuratorischen Team, dem sowohl objekt- als auch vermittlungsorientiert arbeitende Kolleg*innen angehörten[5] und waren uns rasch einig: Seit der Waldheim-Debatte 1986, dem „Bedenkjahr“ 1988 und dem 1991 erfolgten ersten Bekenntnis eines amtierenden Bundeskanzlers zur Mitverantwortung von Österreicher*innen an den Verbrechen des Nationalsozialismus hat sich in Österreich in Sachen Aufarbeitung der und Auseinandersetzung mit den NS-Verstrickungen vieles bewegt:[6] Etwa die Gründung des Österreichischen Versöhnungsfonds, der Errichtung der Jüdischen Museen in Hohenems und Wien sowie die Restitution(sforschung), aber auch die Zunahme der Artikulation von rechtsextremen Weltdeutungserzählungen im Umfeld von Krisenerfahrungen seit 2020, um nur einige Beispiele herauszugreifen. Wo aber stehen wir heute? Einerseits ist 2022/23 das Ende der Ära der Zeitzeug*innen nahe – eine Generationenschwelle – und gleichzeitig übernehmen in Städten, am Land und in Gemeinden unterschiedliche Generationen und Initiativen in der Verantwortung für die Aufarbeitung der Verbrechen der Nationalsozialist*innen sowie für die Auseinandersetzung mit Zeichen der Erinnerung in Form von Straßennamen, Gedenktafel und Denkmälern. Erinnerung pulsiert, bewegt und verändert sich laufend – genau das wollen wir versuchen im neuen Ausstellungsbereich „Erinnern: Die Gegenwart der NS-Vergangenheit“ zu vermitteln.

Erinnerungspolitische Transformationen dezentrieren: Veränderungen von den Rändern aus

Wichtig erschien uns dabei, nicht nur die Zeitlichkeit zu berücksichtigen und stärker Entwicklungen der letzten Jahre zu berücksichtigen, sondern auch eine Verortung mit zu berücksichtigen und damit sowohl metaphorisch als auch geografisch eine Dezentrierung der Darstellung und Diskussion von Erinnerungskulturen in Österreich zu versuchen. Pate gestanden bei dieser Idee war die Beobachtung, wie sich seit den 80er-Jahren Transformationen in den Erinnerungskulturen nicht nur durch sprichwörtliche Setzungen im urbanen Kontext ermöglicht wurden, sondern durch lokale Initiativen häufig im kleinstätischen, ländlichen Raum oder im Rahmen von Community Arbeit in größeren Städten erreicht wurden[7]: Obwohl die Leistungen schon der vor inzwischen vierzig Jahren sozialisierten Generation of Memory besonders von Heidemarie Uhl früh auch als zentraler Faktor der Herausbildung der österreichischen Mitverantwortungsthese in Forschungszusammenhängen berücksichtigt wurden,[8] werden die im Detail dann häufig komplexen Prozesse der Aushandlung dessen, was das vor Ort und im Zusammenhang überschaubarer Communitys bedeutet unserer Auffassung nach in der Forschung über österreichische Erinnerungskulturen nicht ausreichend diskutiert. Während unsere Rolle als Museum hier bedauerlicherweise nicht darin bestehen kann, das durch ein Herausarbeiten der Interdependenzen zwischen den Debatten um solche bottom-up entwickelten Erinnerungszeichen und den „großen“ Verschiebungen und Veränderungen im erinnerungspolitischen Feld zu kompensieren, möchten wir als kuratorisch Arbeitende hier stattdessen kurz pars pro toto einige Beispiele aufzählen, die für uns eine zentrale Motivation waren, ein dezentrierendes Display zum Ausstellen solcher Diskussionen zu entwickeln, bevor wir eben dieses vorstellen.

Gerade in den letzten Jahren sind um eine Reihe von groß dimensionierten Erinnerungszeichen Debatten entstanden, prominent erstens rund um die Fertigstellung und Eröffnung eines zentralen Denkmals der Republik für Shoah-Opfer in Wien (genannt Gedenkstätte für die in der Shoah ermordeten Jüdischen Kinder, Frauen und Männer aus Österreich), das auf die Initiative eines einzelnen Shoah-Überlebenden zurückging und in seinem Entstehungscharakter daher auch sehr eindrücklich die Grenzen von bottom-up vs. top-down-Vorstellungen vor Augen führt. Ein zweites Beispiel ist die analog dazu entstehende Debatte um das zentrale Mahnmal für die Romani Opfer der NS-Verfolgung, das ebenfalls für Wien gefordert wird. Am meisten Aufmerksamkeit lag in öffentlich-medialen Debatten jedoch jedenfalls auf ein Denkmal, das keinen unmittelbaren Bezug zur NS-Herrschaft hat, nämlich das Denkmal für Bürgermeister Karl Lueger, das zum zentralen Ort wurde, an dem internationalen Denkmaldebatten nach den Black Lives Matter-Protesten von 2020 in Österreich geführt wurden – unter prominenter Beteiligung von Shoah-Überlebenden und jüdischen Aktivist*innen. Daneben aber waren es gerade die nicht in Wien angesiedelten Projekte und Initiativen, die die Bedingungen und Grenzen von Erinnerungspolitiken verschoben. Diese Grassroots-Initiativen stehen unter starkem Widerstand einzelner oder institutionell gebundener örtlicher Player und sind im Gegensatz zu urbanen Beispielen häufiger Prozesse, die mit der Errichtung eines sichtbaren Zeichens nicht abgeschlossen sind, sondern jedenfalls mit weiter geführten Auseinandersetzungen einher gehen. Beispielsweise scheiterten burgenländische Romani NGOs mit ihrer Forderung nach grabkreuzartigen Erinnerungszeichen auf lokalen Friedhöfen des Burgenlands in den Jahren nach 2006. Gestaltet von lokalen Romani Kunstschmieden, sollten diese Kreuze dezidiert private eher als öffentliche Denkmäler sein und überlebenden wie nachgeborenen Angehörigen einen Platz geben, an dem sie ihre Kerzen in Gedenken für die ermordeten Verwandten anzünden zu können. Es scheint bezeichnend, dass exakt diese sehr unmittelbare und konkrete, nicht abstrahierte Form der Erinnerungszeichen nur in einzelnen Fälle von 2006–2009 umgesetzt wurde, während in den letzten Jahren die Form des klassischen, meist viele Opfergruppen auf einmal ansprechenden und an einem zentralen öffentlichen Ort errichteten künstlerischen NS-Opferdenkmals in den gleichen Orten weit verbreitet wurde.[9] Solche Ergebnisse der lokalen Auseinandersetzung mit dem „Zivilisationsbruchs Auschwitz“[10] bewegen sich also nicht entlang einer hierarchischen linearen Logik von urbanem Zentrum zu Region. Ähnliche Beispiele lassen sich vielfach und in allen Regionen Österreichs identifizieren, darunter etwa die folgenden unterschiedlich prominenten Beispiele: In der Vorarlberger Gemeinde Silbertal wurden NS- und Kriegserinnerung nach dem Aufdecken der SS-Mitgliedschaft eines lokalen Soldaten in einem völlig neu gestalteten Denkmal so aufgegriffen, dass auch die bisherige Gestaltung sichtbar wird.[11] Im Rahmen eines Kunstfestivals legte 2012 eine vor Ort wohnende Kuratorin bei Murau in der Obersteiermark die Geschichte eines Lagers und der dort internierten Romani Zwangsarbeiter offen, die allesamt ermordet worden waren.[12]Seit 2015 erproben zwei Künstlerinnen mit dem Format Interferenzen neue Möglichkeiten der Auseinandersetzungen mit ephemeren und materiellen Formen der Erinnerung an NS-Verfolgung im Loibltal bei Ferlach in Südkärnten.[13] Einen Sonderfall schließlich stellen Beispiele von NS-Architektur dar, die in letzter Zeit in zwei Fällen zu Debatten unter sehr verschiedenen Bedingungen geführt haben. In Innsbruck haben Bauarbeiten am heutigen Landhaus, das als NS-Gauhaus geplant und errichtet worden war, zu Kontroversen um den Auftrag von Denkmalschutz geführt hat, dessen wichtige Erweiterung auf NS-Bauten ja nicht die bruchlose Fortschreibung von NS-Formensprache und ihrer Prämissen bzw. die Verhinderung demokratischer, antifaschistischer Interventionen bedeuten muss. Erneut ist es hier ein Beispiel nicht aus dem urbanen, sondern aus dem ländlichen Raum, in dem diese Auseinandersetzung über Jahre vor Ort geführt wurde und Forschungs- mit sozialen und Kulturperspektiven zusammengedacht wurden, nämlich in einer Initiative zur Aneignung des „Anschlussdenkmals“ im burgenländischen Oberschützen.[14] All diesen Beispielen ist gemeinsam, dass innovative Ansätze häufig in ergebnisoffenen Prozessen, die sprichwörtlich vor Ort ausgetragen werden und die Multiperspektivität von Erfahrungen und Interessen berücksichtigen, entwickelt wurden und weder aus einer hegemonialen Perspektive top-down noch gewissermaßen abschließend geklärt werden können.

Kuratieren als demokratische Auseinandersetzung, dynamisches Ausstellen aktueller Fragen

Im Zentrum des neuen Ausstellungsbereichs in der hdgö-Hauptausstellung befindet sich daher eine digitale Landkarte der „Baustellen der NS-Erinnerung“, die sowohl in diesem materiellen als auch im virtuellen Museumsraum der hdgö-Webplattform verfügbar ist und. sich aus Bild- und Texteinträgen von Besucher*innen speist, die diese dort zur Diskussion stellen.[15] Die Kriterien für Ein- oder Ausschluss von solchem User Generated Content sind inhaltliche Bedingungen in Bezug auf Thema und Region sowie die Übereinstimmung mit rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen (Urheber*innenrecht, Personenschutz, Datenschutz). Inhaltlich ist an der Web-Ausstellung „Baustellen der NS-Erinnerung“ der dezentrierende Ansatz und der Fokus auf Kontroverse und Widerspruch zentral. Die Oberfläche der Ausstellung zeigt eine Österreich-Landkarte, mit der wir der geografischen Lage unseres Museums in der Neuen Burg in Wien eine relativierende Perspektive auf alle Regionen Österreichs gegenüberstellen. Mit heutigem Stand sechs Wochen nach dem Launch scheint sich dieser Ansatz angesichts zahlreicher Einreichungen besonders für Grenzregionen (in allen Himmelsrichtungen) bewährt zu haben, werden damit doch nicht nur die spezifischen Bedingungen der regionalen Geschichtspolitiken in den Südkärnten und dem Waldviertel sicht- und diskutierbar, sondern auch die Marginalisierung von regionalen Opfergruppen wie den Burgenland-Rom*nija und Kärntner Slowen*innen oder Beispiele für lokale Initiativen vergleichbar, die als hochemotionalisiert und teils tabuisiert geltenden Themen aufgreifen. Mit der Frage nach der Einordnung in fünf Kategorien („Hier soll etwas entfernt, kommentiert, umgestaltet, verändert werden oder unverändert bleiben“) versuchen wir der Breite der möglichen Positionen gerecht zu werden und die Debatte zu ein- und demselben Ort vorzustrukturieren. Das Ziel der Auseinandersetzung ist also nicht die Identifikation der (moralisch oder inhaltlich) „richtigen“ Position, sondern das Führen einer Debatte und das Offenlegen von Argumenten.

Dass Erinnern eine Form eines Ausverhandlungsprozesses ist, verdeutlicht augenscheinlich auch die künstlerische Installation „Ringen um Erinnerung“ von Iris Andraschek und Anna Artaker, die über dem Themenbereich schwebt. Vier ineinander verschlungene Ringe mit LED-Leuchtlaufschriften geben vier unterschiedliche gesellschaftliche Akteur*innengruppen Raum, ihre Positionen in der Verhandlung um Erinnerungspositionen sichtbar zu machen. Während der erste Zitate von Überlebenden der NS-Verfolgung mit geringer Geschwindigkeit sprichwörtlich leuchten lässt, visualisiert der zweite Ring geschichtspolitische Schlagzeilen aus den öffentlich-medialen Debatten der letzten zehn Jahre. Der dritte repräsentiert die Zivilbevölkerung, die sich an der Diskussion der digitalen Landkarte der „Baustellen der NS-Erinnerung“ beteiligt und mit dem vierten Ring schreiben sich Schulklassen und Gruppen ins Museum ein, die den Vermittlungsworkshop „Was tun?“ im Haus der Geschichte Österreich besuchen. Daneben steht im Zentrum des Ausstellungsbereichs ein „Message-Board“, an dem vor Ort im Museum von Besucher*innen für Besucher*innen in klassischer Papierform Botschaften oder Fragen hinterlassen werden können und damit vor Augen führen, dass Geschichte von vielen geschrieben wird. Hier besteht eine entscheidende konzeptionelle Weiterentwicklung bisher von uns eingesetzten ähnlichen Formaten darin, dass in einem moderierten Dialog Besucher*innen sowohl zum Formulieren von neuen Fragen als auch Antworten auf bestehende eingeladen werden.

Diversifizierung statt Homogenität, Multiperspektivität statt Teleologie

Den Rahmen für diese in der jeweiligen Gegenwart angesiedelte Auseinandersetzung bilden vier Ausstellungsbereiche, die anstatt der Zentralsetzung eines Ereignisses oder Prozesses eine Akteur*innenzentriertheit und damit auch eine Multiperspektivität auf viele verschiedene Prozesse entgegensetzen. Geclustert sind diese in vier semantisch bewusst unscharf gefassten Ausstellungsteilen, die jeweils chronologisch quer durch die Geschichte der Zweiten Republik schneiden und auf dem äußerst begrenzt vorhandenen Raum exemplarisch bekannte mit bislang marginalisierten Geschichten konfrontieren.

„Opfermythos: spät entkräftet“ führt kompakt die lange Geschichte der jahrzehntelangen Ausblendung der österreichischen Mitverantwortung vor Augen. Im Gegensatz zur bisherigen Präsentation haben wir dabei in Hinblick auf den spärlich vorhandenen Platz auf zentrale Ikonen der österreichischen Erinnerungsgeschichte verzichten müssen, wie etwa die nach Entwürfen von Lörinc Borsos gestaltete Briefmarkenserie „Niemals vergessen!“ zur 1946 im Wiener Künstlerhaus stattfindenen gleichnamigen Ausstellung, das „Rot-weiß-Rot“-Buch oder eine „O5-Schleife“ ungeklärter Provenienz aus dem Dokumentationsarchiv des Österreichischen Widerstands. Gemeinsam mit der im April 1945 noch in Bratislava gedruckten Plakate „Wieder frei!“ mit dem Motiv des Stephansdoms mit der rot-weiß-roten Fahne haben wir uns also entschieden, die ganze Reihe der unleugbar wichtigsten Objekte des frühen antifaschistischen Grundkonsenses nicht mehr auszustellen, weil dieses Narrativ nicht mehr in dem Ausmaß als Reibefläche für produktive Fragen an die Gegenwart zu taugen scheint wie eine Gegenüberstellung des Staatsvertrags als Gründungsmythos mit der fiktionalen Entschuldungserzählung des Spielfilms 1. April 2000, der inzwischen breit anerkannten kritischen Initiativen in der Waldheim-Debatte mit den weitgehend vergessenen Vorarbeiten dafür durch marginalisierte Akteur*innen wie etwa Elfriede Jelinek in ihrem schon 1982 in Deutschland uraufgeführten Stück Burgtheater oder der Präsentation einer differenzierenden Perspektive auf das Bekenntnis von Bundeskanzler Franz Vranitzky 1991, das wir österreichische Reaktion auf einen schon davor beginnenden europäischen Paradigmenwechsel präsentieren.

Der Abschnitt „Anerkennung: lange verweigert“ vermittelt die Perspektive der Überlebenden der NS-Verfolgung und ihren Nachkommen zu ihren Erfahrungen im Umgang der Behörden der Republik und der Mehrheitsgesellschaft mit ihren Versuchen der Anerkennung von Leid und der Entschädigung von erfolgtem Unrecht sowie zur diskursiven Positionierung von NS-Verfolgung in der Zweiten Republik ganz allgemein. Nicht zufällig haben wir dabei Objekte aus dem aktivistischen bzw. künstlerischen Umgang von Opfergruppen selbst ausgewählt, allen voran die zweifache Wiedergabe jenes Baumes in Bergen-Belsen, dessen Rinde und Harztropfen der jungen Romani Auschwitz-Überlebenden Ceija Stojka das Leben im nicht mehr versorgten KZ vor der Befreiung gerettet haben – einmal ist diese Darstellung auf einer Zeichnung Stojkas selbst zu sehen, einmal auf einem an Stojka überreichten Mantel, mit dem sich eine NMS-Klasse bei der Zeitzeugin für einen Workshop bedankte. Daneben vermitteln Objekte aus dem Kontext von HOSI-Protesten den langen Kampf um Anerkennung bestimmter Opfergruppen, der im Fall für ihre sexuellen Beziehungen verfolgten Frauen ja bis in die Gegenwart andauert oder mangelhaft ausgeprägtem Unrechtsbewusstsein, der mit einer Assemblange von Souvenirs mit dem Motiv des Bildnis Adele Bloch-Bauer von Gustav Klimt die andauernde Vermarktung eines Bildes als Österreich-Symbol anschaulich macht, das als unrechtmäßiger Besitz eines Bundesmuseums auch Jahrzehnte nach seiner Restituierung umsatzstark ist.[16]

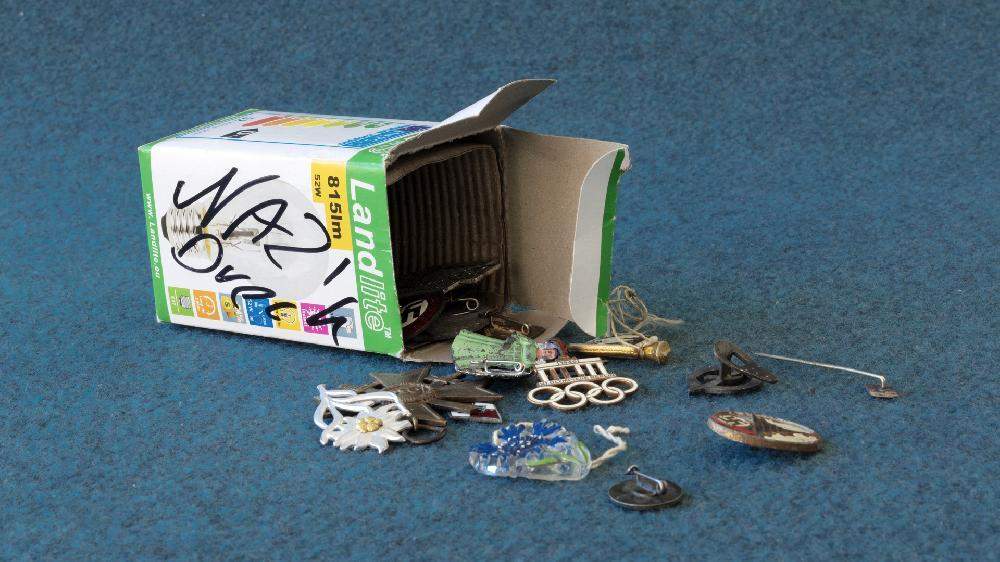

Unter dem Titel „Kontinuitäten: kaum offengelegt“ richten wir den Fokus auf das lange Nachwirken der NS-Ideologie sowohl anhand von Personen-, Institutionen- als auch Inhaltskontinuitäten. Auch wenn der Bogen hier äußerst weit vom Programm der Architektur von Kriegerdenkmälern über Rassismus in Museen bis zu NS-Massenware in den Nachkriegskindheiten gespannt ist, sind es doch zwei prominente Fälle von nicht nur fortgesetzten, sondern sogar an Relevanz gewinnenden Karrieren, die diesen Bereich rahmen: Charakteristisch für unsere kuratorischen Entscheidungen war in beiden Fällen die Wahl der Objekte, die nun die Affäre um den NS-Psychiater Heinrich Gross über das Engagement seines Opfers Friedrich Zawrel erzählt und die Aufdeckung der SS-Mitgliedschaft von Friedrich Peter verwendet, um das enorme Verdienst Simon Wiesenthals in der Recherche solcher Karrieren, aber auch den damit verbundenen nachhaltigen Rufmord sichtbar zu machen.

Der Bereich „Antisemitismus: tief verankert“ schließlich vermittelt einen Überblick über die Kontinuität der verschiedenen Formen von Feindschaft gegenüber als jüdisch betrachteten Personen sowohl in Bezug auf Beispiele für typische Fälle wie Friedhofsschändungen als auch anhand zentraler Zäsuren wie etwa anhand der Debatte über Shoah-Vergleiche im Umfeld von Coronamaßnahmen-Gegner*innen. Systematischer als in den anderen Kapiteln haben wir hier die Historisierung der Beispiele betrieben und jeweils aktuelle mit weiter zurückliegenden Fällen bewusst konfrontiert sowie Beispielsammlungen zur vertieften Auseinandersetzungen so gestaltet, dass sie je zwei Fälle aus jedem Jahrzehnt ebenso zeigen wie einen beispielhaftes Bild der Breite von antisemitischen Erfahrungen von jüdischen Jugendlichen und ihren Einsatz dagegen.

Ausblick

Mit dieser kuratorisch-vermittlerischen Herangehensweise und der Teamarbeit, zu deren hoher Qualität auch beitrug, dass die Gestalterin Teil der museumsinternen Arbeitsgruppe war, versuchten wir einen zukunftsweisenden Weg einzuschlagen, der – das ist nicht nur Erwartung, sondern auch Forderung – in einigen Jahren überarbeitet werden muss, selbst wenn er durch die Zentralsetzung dreier dynamischer Elemente die Gegenwartsorientierung und Veränderlichkeit in den Vordergrund rückt und dem Publikum je nach dem Zeitpunkt ihres Besuchs stets neue bzw. erweiterte Inhalte präsentiert. Dass die österreichweit geführten Diskussionen über die Formen und Praktiken des Erinnerns am Beginn der 2020er vielleicht so vielfältig sind wie nie zuvor und Widerspruch in höherem Maß zulassen, werten wir als optimistisch stimmendes Indiz dafür, dass mit dem Ende der Ära der Zeugen*innenschaft das Erinnern nicht endet und eine nächste Generation wiederum neue Formen finden wird, um jeweils virulente Fragen an die Vergangenheit zu stellen.

[1] Vgl. Stefan Benedik, Eva Meran, Monika Sommer: Haus der Geschichte Österreich – das zeitgenössische Museum als Diskussionsforum und Prozess. In: Rainer Wenrich, Josef Kirmeier, Henrike Bäuerlein, Hannes Obermair (Hg.): Zeitgeschichte im Museum. Das 20. und 21. Jahrhundert ausstellen und vermitteln, München 2021, 79–92.

[2] Vgl. Sommer, Monika: Zeitgeschichte und Museen, in: Gräser, Marcus/Rupnow, Dirk (Hg.): Österreichische Zeitgeschichte – Zeitgeschichte in Österreich. Eine Standortbestimmung in Zeiten des Umbruchs, Wien 2021, S. 798–825. Dies.: Das Haus der Geschichte Österreich – ein Aufbruch ins Ungewisse, in: Karl, Beatrix/Mantl, Wolfgang/Poier, Klaus et al. (Hg.): Steirisches Jahrbuch für Politik 2018, Wien–Köln–Wei- mar 2019, S. 111–116. Rupnow, Dirk: Nation ohne Museum. Diskussionen, Konzepte und Projekte, in: Rupnow, Dirk/Uhl, Heidemarie (Hg.): Zeitgeschichte ausstellen in Österreich, Wien–Köln–Weimar 2001, S. 417–463.

[3] Vgl. Bettina Habsburg-Lothringen, Dauerausstellungen. Erbe und Alltag, in: Dies. (Hg.), Dauerausstellungen. Schlaglichter auf ein Format. Edition Museumsakademie Joanneum 3, Bielefeld 2012, 9-20.

[4] Sabine Offe, Dauer ausstellen? Ein Versuch über Zeitbotschaften in Jüdischen und anderen Museen, in: Bettina Habsburg-Lothringen (Hg.), Dauerausstellungen, 45-54, hier 45.

[5] Im konkreten Fall waren das Stefan Benedik, Markus Fösl, Laura Langeder, Eva Meran, Marianna Nenning und Monika Sommer. Die Projektkoordination und Produktionsmanagement verantworteten Anna Bausch gemeinsam mit Nora Pierer, die auch die Gestaltung übernommen hatte. Für das Sammlungsmanagement ist Laura Langeder am Haus zuständig, für Fragen der Konservierung und Restaurierung Petra Süß, für Objekterfassung und Recherchen Antonia Heidl, Johannes Pötzlberger. Für Kommunikation & Verwaltung stiegen Louise Beckershaus, Ann Cathrin Frank, Ildiko Füredi-Kolarik, Karolin Galter, Katharina Kraus, Antonia Plessing in das Projekt ein, ein künstlerischer Beitrag wurde von Iris Andraschek und Anna Artaker entwickelt.

Dirk Rupnow von der Universität Innsbruck und Heidemarie Uhl von der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften begleiteten das Projekt als wissenschaftliche Konsulent*innen, externe wissenschaftliche Recherchen wurden von Bernhard Hachleitner, von Marion Krammer, Caroline Schenk, Margarethe Szeless – WeSearch und von Anna Stuhlpfarrer beigetragen.

[6] Heidemarie Uhl, Transformationen des österreichischen Gedächtnisses, in: Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 29 (2000), 317–341; Heidemarie Uhl, Vom Opfermythos zur Mitverantwortungsthese. In: Christian Gerbel (Hg.), Transformationen gesellschaftlicher Erinnerungen. Wien 2005, 86–130; Heidemarie Uhl, Conflicting Cultures of Memory in Europe, in: Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 3 (2009) 2, 59–72.

Heidemarie Uhl, Schuldgedächtnis und Erinnerungsbegehren, in: theologie.geschichte Beiheft 5 (2012), 193–214. Vgl. dazu auch: Hub Van Baar, The Way Out of Amnesia?, in: Third Text 22 (2008) 3, 373–385.

[7] Pirker, Peter, Johannes Kramer and Mathias Lichtenwagner. “Transnational Memory Spaces in the Making: World War II and Holocaust Remembrance in Vienna.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 32 (2019): 439 – 458; Johler, Birgit, Katharina Kober, Barbara Sauer, Ulrike Tauss, and Joanna White, A Local History of the 1938 “Anschluss” and Its Memory: Vienna Servitengasse, in: Günter Bischof, Ferdinand

Karlhofe, R. Samuel Williamson Jr. (Hg.): 1914. Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I,

2014, 293–320.

[8] Heidemarie Uhl, Learning from History? Why European Societies Remember the Holocaust Today, in: Témoigner. Entre histoire et mémoire, 126 (2018), 48–53, DOI: 10.4000/temoigner.7157

[9] Von 2006–2009 wurden fünf Denkmäler für Rom*nija, meist auf Friedhöfen, eingeweiht (Kleinpetersdorf, Mattersburg, Kleinbachselten, Unterwart – sowie ein zentrales Denkmal für alle NS-Opfer in Neudörfl).

2014 bis 2019 folgten: Goberling (alle Opfergruppen), Jois (alle Opfergruppen), Mörbisch (Jüd*innen und Rom*nija), Jabling (Rom*nija), Sulzriegel (Rom*nija am Friedhof), sowie alleine 2020–2022: Oberpullendorf (alle Opfergruppen), Pamhagen (alle Opfergruppen), Stegersbach (Rom*nija), Langenthal (alle Opfergruppen) sowie in der von einem besonders öffentlich geführten erinnerungspolitischen Konflikt geprägten Gemeinde Kemeten (Rom*nija).

[10] Vgl. Heidemarie Uhl (Hg.), Zivilisationsbruch und Gedächtniskultur. Das 20. Jahrhundert in der Erinnerung des beginnenden 21. Jahrhunderts. Innsbruck et al. 2003.

[11] Weber, Wolfgang. Von Silbertal nach Sobibor : über Josef Vallaster und den Nationalsozialismus im Montafon<br /> Feldkirch: Rheticus-Ges., 2008.

[12] Werner Koroschitz, Uli Vonbank-Schedler, Kein schöner Land NS-Opfer in Murau, Murau 2012.

[13] Rhizom (hg.), Brodi 1, Das Gedächtnis des Ortes, Kraj in njegov spomin. Ein österreichisches Haus erklärt seine Geschichte. Graz 2022

[14] Mindler-Steiner, Reiss, Mindler-Steiner, Ursula, and Reiss, Walter. "Darüber reden... ". : das "Anschlussdenkmal" von Oberschützen : Gedanken, Erinnerungen, Meinungen<br /> Erste Auflage. Oberwart: edition lex liszt 12, 2021.

[15] www.hdgoe.at/erinnerung (abgerufen am 2.5.2023, online seit 15.3.2023)

[16] Wir haben dabei versucht, die Forschungsarbeiten von Andrea Berger gemeinsam mit ihr in eine Ausstellungsform zu übersetzen. Vgl. dazu auch Andrea Berger, Exhibiting Cultural Possessions Looted in the Course of Nazi Persecution, in OeZG 1/2023 [in Druck].